Pierre-Yves Quiviger

« Marc Molk’s french forest », september 2008

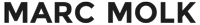

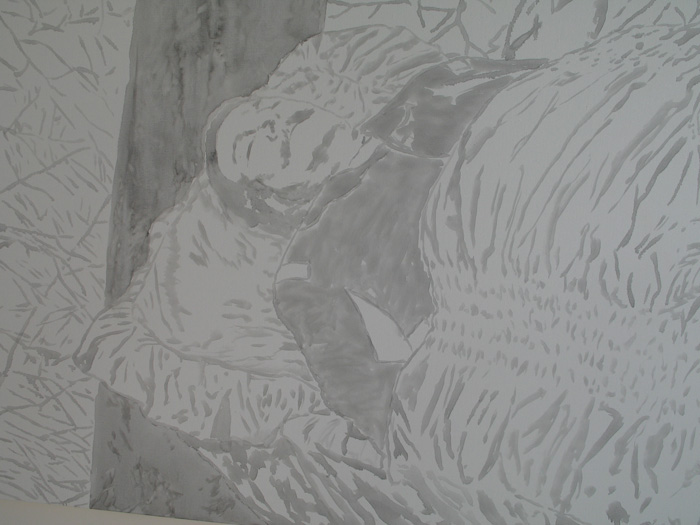

I don’t think I will ever forget the afternoon when Marc Molk showed me this painting, near to completion, in his studio. I stood there, shaking slightly, my voice croaky, and he told me « ça s’appelle La libération sexuelle » (« that’s called Sexual liberation »). And I could see what was plainly a woman with her legs spread, with the origin of the world ; I could plainly see her exposed vulva and the contrast with her upper body kept out of reach behind the crown of thorns, and her tear-stricken face.

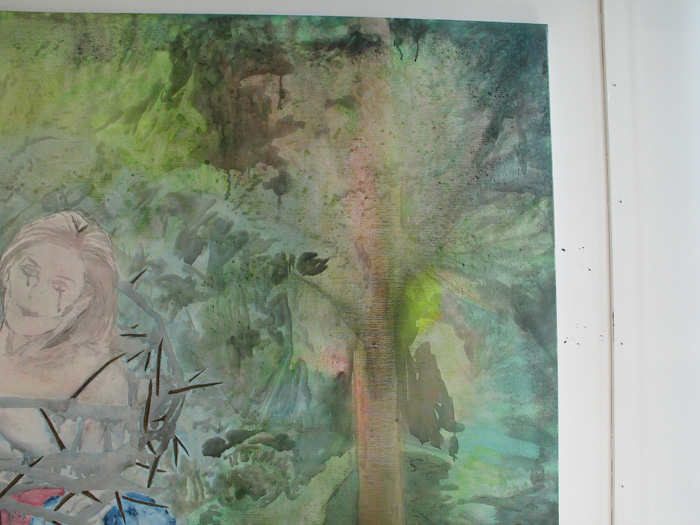

But prior to seeing this woman, I saw her double, behind, and the hinterland, just like in Yves Bonnefoy’s book, which goes back to 1972, the year in which Marc Molk was born. I saw the French forest the likes of which I had not seen since the time of Watteau or Boucher – cloud-vulva, forest-womb.

Before me was the order and disorder of the trunk, the branches, leaves, thought-out tasks, and secrets. It is such an inherently French picture, of this land of peasants, where the town only exists in relation to the countryside, and where urbanity always has something a bit false about it. The sunlight, or the sun itself, is only to be found behind the tree, to the right of the picture. Each branch leads to another world, to a hidden doorway. No, I hadn’t seen a forest such as this since the eighteenth century, with its openess towards the savagery and brazen sexuality lying at the very heart of the world order, and with its melancholia. As such it is the very opposite of the untouched forest : free-thinking and philosophical. Between the face of the Venus in a fur coat and the tree trunk, green, almost black leaves carry on their lives as leaves. Between an example of Liebniz – the rule of the impercptible : no two leaves are the same, no two beings are similar, no two women look alike, each is a world, each story with each woman, each second with each woman, a new dizzying sensation, a territory – and souls of the dead yelling from the cauldrons of hell, hesitating between empaling themselves on the thorns or going back to the ground, the roots and returning to oneself. The woman bears a resemblance to the heroines in Catherine Breillat’s films, such as Caroline Ducey, in Romance, who finds herself being tied up by François Berléand and weeps with joy as, at long last, she experiences the soothing effect of the bindings. This is a French forest, but, of course, it is also a Japanese forest – the crown of thorns is more shibari than Christian, as in this rather fine eighteenth century in France and its fascination for the The Tale of Genji, scenes from which provide the decoration for so many works of art in furniture. One day, Molk will paint Marie-Antoinette. He has no option, it is his chosen subject, everything points him in that direction – needless to say it would have to be a Marie-Antoinette in bondage. Yes, the crown of thorns is full of knots, entwined, and the bruise around each thorn is less the blood-red bruise of Bataille’sBleu du ciel (Blue of Noon) than that of soft rope tied round milk-white skin. These are thorns which bring tears of joy rather than the shedding of blood, and which brush and scrape the surface but do not make the blood run.

The woman at the centre of the picture isn’t sad, or at least… she is no more sad than any other eighteenth century princess, courtesan or peasant girl. Her pain is of the joyous kind arising from the understanding of how things are. The world around her is not outside of her. She is its most lively manifestation, its charming, burning reflection. On her right, we find a sexual organ, in all its immensity, closed and bald, an untarnished fleece. It contrasts with her mound, at the top of her slightly plump thighs, as are her calves and heels (no, it is always in keeping with the century) : the naked, shaven genitalia of a woman standing up, as big as the heroine’s body in its entirety. Shades of yellow, pink, orange and, lastly, black and green are present, as though it was necessary to construct the continuity of the forest and femininity (our thoughts turn to Beauvoir, in Mémoires d’une jeune fille rangée (Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter) , and to the discovery of sensuality in the ground, trees, wind, mushrooms and in the dew). On her left, where the brown and beige of the trunk turn pink and the black branches become a Chagallian blue, the outline fades and becomes watery. This is no longer the hinterland, but that other place. If we turn to the roots, if we abandon transcendentalism in order to become grounded once again, peasant-like, we see that in actual fact the tree seems to have no roots. In the midst of this almost vaporous haze which links the fur coat to the tree-trunk, we cannot make out anything which might be able to withstand such an unlikely tree as this.

The fur coat is the gateway to the domain of artifice and playfulness. In “real life”, no animals have blue hair, there is no such leather which is pink (the coat has no lining, it is worn in its raw state) and as liquid as this, or so full of waves. The pelvis, vulva, thighs, calves, heels and the right foot lie beneath the bondage-type ring of thorns. Although the upper body is prevented from coming into contact with the air by virtue of the knots and thorns, the spread legs lay on the coat of an imaginary bear.

Tying up the body leads to sexual gratification, and to the metaphysical (which is the same thing), and to a reinvention of the body – recreating in an artificial way the body’s natural state, together with the violence, submission, and domination – thedeconstructed body ; the freed body, itself, needs to work with the naturalness of the artifice in order to experience, via the imagination, the carnal delight which is derived from another, more cerebral, less sensual, form of the metaphysical – the double body. The coat only exists “in the mind”, it is a volcano-coat (interior) and tornado-coat (exterior) – the painter brings out what comes from within the freed body, what the freed body invents, its activity. The fact that it is fur brings us to Sacher-Masoch and to the idea of a form of submission which is the supreme form of domination, according to the tried and trusted formula, in as much as this submission is the inventor of abandonment, the will to end will.

There is a forest which closes in and a forest which liberates, a forest which welcomes me and a forest which I bring forth. However, this double – or rather triple – body: the true body, the symbolic body (bound), and the imaginary body (freed) – is that of one woman only. She is both young and old (her hair is as brown as it is blonde or white), thin (almost corseted waist, not particularly shapely hips) rounded (bum, thighs, breasts), and both happy and unhappy.

The picture is entitled « La libération sexuelle » – we might have known : it is a pleonasm.

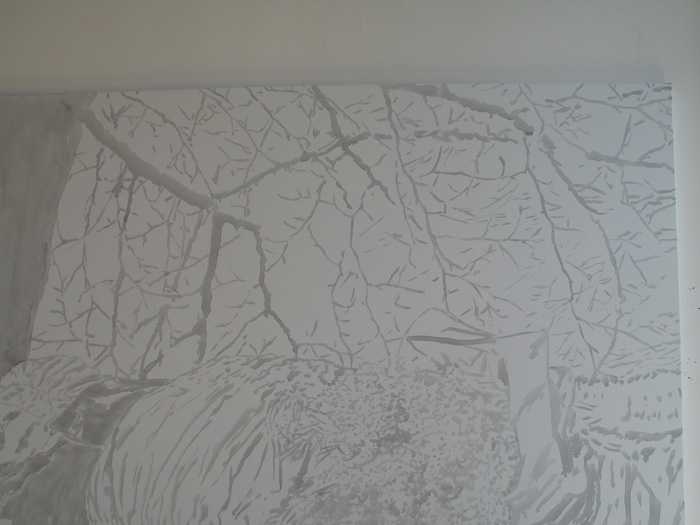

Marc Molk’s French forest is, at long last, La troisième république (The Third Republic). I don’t know if Molk is going to finish the painting ; in reality, I hope not. In its present state, it is infinitely Japanese and sylvan, and it should remain so. Perhaps a few strokes of yellow on the bunch of mimosa, in the middle, but apart from that there is nothing to be touched up or added ; anything added here would undermine its strength and what is self-evident about it. The way I see it is: Marc Molk has spent years constructing himself, failing, and trying and then, one day, as with the aged, he began to understand things. He understood that things were finished, done, completed. This enabled him to understand roughly how it works, a woman, and then it’s La libération sexuelle – and it’s not difficult: it works like a world, a reflection of the totality of the world. It is not a piece of the world, as men are, it is a world, a reading of a world, which gives rise to a more elevated liberty, a greater instability and an increased capacity for acceptance. Following this, he has been in a position to become old and wise and serene (well almost) : and this is where he has begun to accept what terrified him previously, death, the corruption of things, and the irreversible. La troisième république is the painting of a dead man in the same way that La libération sexuelle is a painting of a woman, which is the objective and subjective genitive in both cases : Molk became a woman in order to paint La libération sexuelle, he became a dead man in order to paint La troisième république.

Being dead means no longer needing colour. It is : a few lines, getting finer and finer, and the canvas in all its refined, white tenderness. The trunk is not dead, but the leaves have fallen, things go on, it’s no big deal, it’s actually quite funny. Marc Molk picks up a brush, and follows the world order, he bows down, he is resigned to it. He does nothing, he obeys. He is calm, at last. His mind is at rest. He might cry when he comes to paint the instant when the dead twig comes away from the branch and falls to the ground but remains suspended for a few seconds. Thus, he is like the poet in Inoué’s Fusil de chasse (The Hunting Gun) who sees, during the hunter’s walk, from afar, the “bed of the pallid torrent”. Or he is like Barthes, in L’empire des signes (Empire of Signs), he who wrote so much and in a sometimes complacent way, but who finally comes to understand the power of silence and sobriety. Heavens, how fiendishly Japanese this painting is, and how in each of the painter’s gestures we feel the serenity of ancient gestures, painstakingly constructed.

If we haven’t seen anything of much interest in France since the eighteenth century, apart from two or three isolated examples here and there (Gaugin, Proust etc.), it is perhaps because of overlooking Japan, resulting from a more general fear of asianism and the obsession with atticism. There is an art to the strokes used in this picture which is admirable : we follow each one like a road leading us not to a world but, on this occasion, but to an end. There are a thousand tiny deaths in this picture which seem to be saying to the colour (except, perhaps, for the mimosa, we’ll see, he’s the one who paints, all I do is to dream about it) “don’t touch me, I am all the more beautiful for not having been touched by colour, I am like a Japanese cherry tree flower carried on the wind, or Malherbe’s rose which was consolation to Du Perrier, which was there before you were born and which will be there even after your children are dead and which, however, only exists for as long as the time it it takes for you paint me”.

This is how I see it (thus) : Marc Molk paints each stroke, then sits down on the floor of his studio, his bum on the floor (like me, as I write this piece, today the 18th September 2008), he drinks some tea, he is happy, the road has been long, he has travelled the length of life’s long path, and now he is dead (in a satori way) – in other words : he is fine, and he blows you a kiss and he sends you his regards.