Pierre Malachin

« Eros’s Tears », may 2012

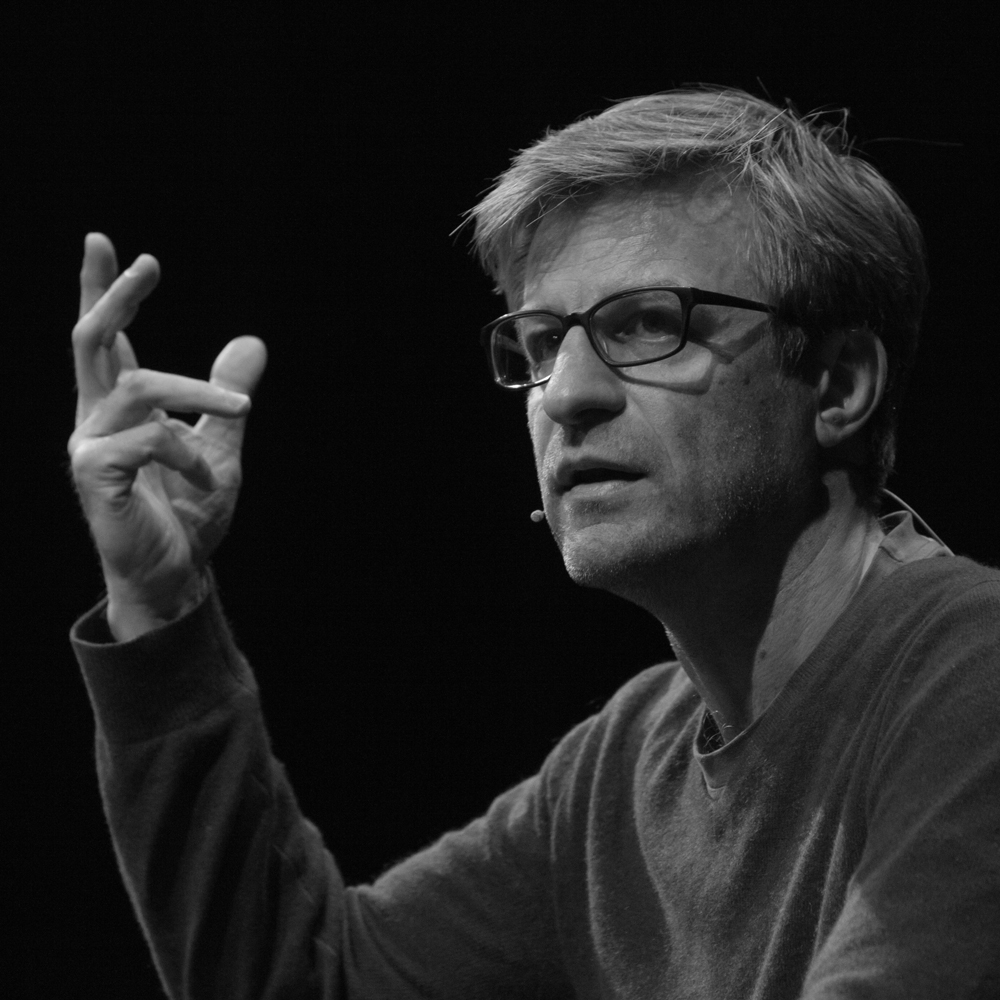

Evidently Marc Molk’s paintings put us into an uncomfortable and almost anachronistic feeling of romanticism stemming from a state of upheaval. Indeed, this self-taught artist paints unchanging, universal subjects: death, war, the possibility and impossibility of loving, friendship, themes which continue to extend beyond the academicism of art history.

These subjects are, however, merely pretexts for the unfurling of Marc Molk’s unique pictorial universe in which we find pastels intermingled at random with vivid colours, traditional techniques with virtuoso technical inventions, and pared-down compositions with baroque ones.

Jean-Yves Jouannais

« Everything gets mixed up in my mind », Interview, march 2011

Jean-Yves Jouannais : I am most intrigued by the way you insist on giving a number of your canvasses an esoteric title, destined for a wide audience, and an esoteric, confidential, title. Even if you appear to do so in a playful way, I wanted to know if the images you create give themselves over to being deciphered via this double logic. Within these images is there, if we take a classic esoteric image, a shell and a kernel, a body and an inner core, or marrow all at the same time ?

My reading of your partly auto-fictional book, Pertes humaines (Human Losses), has prompted me to conjure up a hypothesis. It is as though the core or marrow of your pictures was essentially comprised of matter rooted in the emotional turmoil of childhood and adolescence, whilst the shell or body was comprised of its adult, mature, and politicized manifestation. In particular, my mind turns to Noces Vermeilles (Blood Wedding) alias “La Vie de ma soeur” (The Life of My Sister), but also to La Troisième République (The Third Republic) alias “La Mort de Daniel” (The Death of Daniel).

Eloïse Lièvre

« Marc Molk’s wet drawings », january 2010

If we must talk, write, wrap in words, weed, describe, then the first thing to note is the chosen technique, its intrinsic melancholy, its “streaming with tears” quality. Marc Molk makes “wet drawings”.

It takes courage to abandon carefully crafted, finely drawn compositions that greedily ate up so much time and precision to the workings of water. I have been told several drawings, many drawings, did not survive. One can’t command water to make a right or a left, one almost can’t. The lines dissolve, lose their precision, gain fluidity, complexity. Sometime it’s hair let loose, forming a sort of mane. Sometimes it’s the traces of the pattering of tiny and violent raindrops, breaking up “the thread of the line”. The thread remains, though; sometimes only the ghost of a trail, nearly orange.

Pierre-Yves Quiviger

« Marc Molk’s french forest », september 2008

I don’t think I will ever forget the afternoon when Marc Molk showed me this painting, near to completion, in his studio. I stood there, shaking slightly, my voice croaky, and he told me « ça s’appelle La libération sexuelle » (« that’s called Sexual liberation »). And I could see what was plainly a woman with her legs spread, with the origin of the world ; I could plainly see her exposed vulva and the contrast with her upper body kept out of reach behind the crown of thorns, and her tear-stricken face.

But prior to seeing this woman, I saw her double, behind, and the hinterland, just like in Yves Bonnefoy’s book, which goes back to 1972, the year in which Marc Molk was born. I saw the French forest the likes of which I had not seen since the time of Watteau or Boucher – cloud-vulva, forest-womb.